Cowboys and Indians: Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

Some quick notes on aspects I haven't so far seen discussed.

The title's reference to Sergio Leone is obviously a bit more polysemic than its predecessors, the film being about Hollywood storytelling, about how Hollywood does 'once upon a time.' We might note here the movie's much vaunted rewriting of history and that 'Hollywood ending' and 'fairytale ending' are virtually interchangeable.

A hefty tonnage of film references naturally get us there, detailed exhaustively elsewhere by now, but also referencess to the forms of moving image presentation itself: lots of curtains and proxy screens. Notably, in one of the films within the film, Di Caprio's protagonist Rick Dalton is revealed to the Nazis he's about to kill by the drawing aside of red curtains, at which point he lets fly with a flamethrower – all this a reference to Tarantino's previous Inglourious Basterds with its burning cinema screen. When Sharon Tate watches her own movie, the cinema screen at one point depicts a TV screen. And at the end, as Dalton's stunt double, Cliff Booth, played by Brad Pitt, is taken off to hospital, the back window of the ambulance is another screen with curtains at the sides, Dalton and Booth observing one another through it in what might be seen, in a film full of artifice, as a particularly Baudrillardian moment. Similarly, Booth lives behind a drive-in movie theatre. The Manson family live on an old Western movie set. And is this the only Hollywood film ever to acknowledge the ubiquity of television in 20th century lives? The characters are immersed. There's no way out of the screen.

Games are being played with storytelling too. The flamethrower is a Chekhov's gun. Dalton, about midway through the film, asked how far along he is with a book he's reading, says, 'About midway,' then notices the book's similarity to his own (mid)life and breaks down in tears. The very first scene in which Booth and Dalton appear – an interview on the set of Dalton's TV show Bounty Law – introduces them as doubles. They seem to be a sort of split protagonist, in the sense that the protagonist is the one who suffers and changes. Booth, in line with his stuntman job, does the suffering, the heroic dangerous stuff, with serious injury by the end, while Dalton does the changing (without really changing internally), coming out of darkness into the warm glow of a happy ending. There's even a rescued princess, Sharon Tate, saved not by the knight coming up the hill to meet her but by the hospitalised Booth, his white knight status evinced by the all-white denim outfit he's acquired in Italy.

This has, of course, been a fairytale shot through with extreme violence (not unlike much of the original Grimm Brothers output then). As Al Pacino's agent character says, complimenting Dalton on one of his movies, 'All the killing. I love it.' Movie violence explicitly begets the final gruesome showdown at Dalton's house, the Manson family members' reasoning that they've grown up watching Hollywood's violence and now they should kill the people (like Dalton) who taught them to kill. Out of nowhere, as the girl who had this idea is horribly maimed but proves uncannily difficult to finish off, the film becomes, briefly, a horror movie.

But the type of storytelling most attended to here is the western. The bulk of Dalton's work is in the genre and the Spahn Movie Ranch where the Manson family live and where Dalton and Booth used to, ahem, shoot is replete with cowboy imagery. In the main house, sculptures of men on bucking broncos seem to be everywhere. Another such appears on the cover of a Time Magazine on the plane when Booth and Dalton fly to Italy to make spaghetti westerns. Also at the Spahn Ranch and later at Dalton's home, Booth encounters a Manson family member called Tex, a real participant in the Tate killings, depicted at the ranch as a sort of hippy cowboy, long-haired, but riding a horse and wearing a cowboy shirt, as well as the black hat of the western bad guy. At the very same time, Dalton is also wearing the black hat, playing 'the tough' (the bad guy) on a western TV show and has himself been kitted out, at director Sam Wanamaker's instructions, to look like a kind of evil hippy – though the makeover of long hair, dark jacket and handlebar moustache makes him more like Manson than Tex. Later, in a scene in Italy, Dalton and Booth both wear buckskin shirts much like Manson was wearing when arrested for the killings.

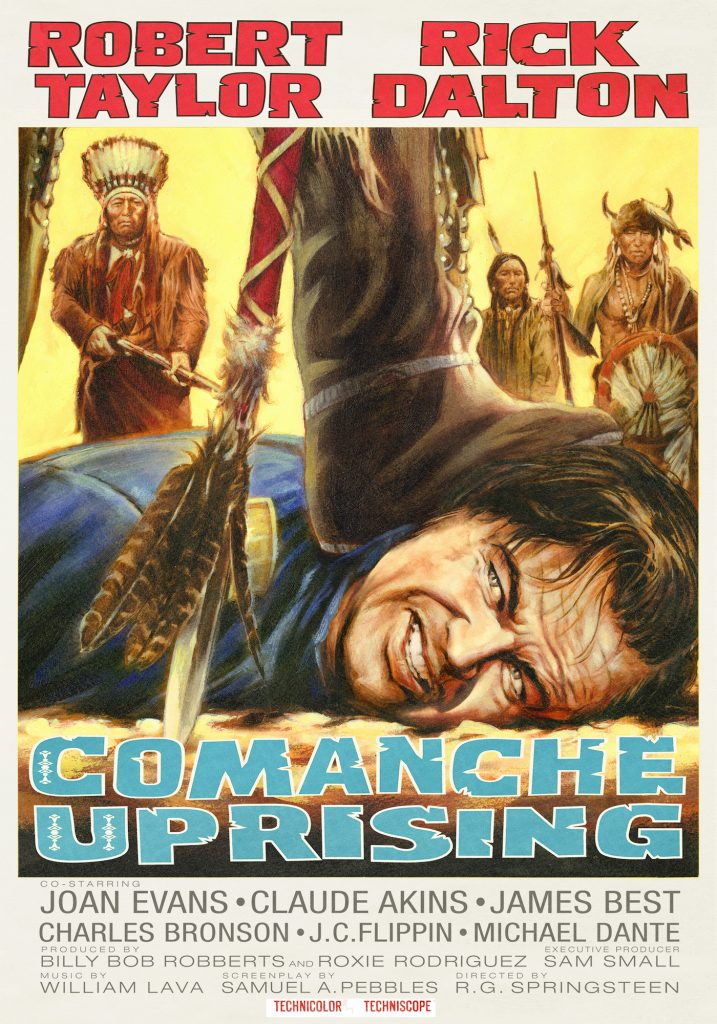

So here's what I think is the key subtext. If there are cowboys, as there are in abundance, are there also Indians? Not nearly as many, but they're here. A street sign reading 'Cherokee' (for Cherokee Avenue) appears early in the film. Later there's a truck with the word 'Navajo' on the side. More tellingly, one of the first shots of Booth is of his feet stepping out of Dalton's car wearing suede moccasin boots. They're given a closeup, while Dalton's cowboy boots appear in the background. A bit later, equally pointedly, the two men pull up in Dalton's driveway, where a large fragment of a movie hoarding sits on breeze blocks, depicting Dalton's face. It is prominent throughout the film, suggesting we should pay attention to it. Inside the house, we briefly see the whole poster. It's for a film called Comanche Uprising and we now see that Dalton as depicted on it, flipped upright in the driveway, is actually lying on the ground, his head held down by another moccasin boot.

Later in Italy, as part of a prolific six-month churn, Dalton will make one other movie acknowledging cowboy-Indian conflict, a movie with an anodyne title, but based on a book called The Only Good Indian is a Dead Indian. This title is the line popularly attributed to Union general Philip Sheridan, a misquote of the quote attributed to him in the book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 'The only good Indian I ever saw was dead,' though he denied he ever said this either. He was responding, or alleged to be responding, to Comanche Chief Tosawi's claim: 'Tosawi good Indian.' We can infer at any rate that the brutality of this title was too much for the moviemakers, even if the story's message remained the same.

This brings us to the nub of the matter, the way the cowboy myth works as American mythology: the violence is relentlessly celebrated while its central role in genocide is fudged. Whether Sheridan said the line or not, there is some rewriting of history here for our Hollywood endings, a certain concoction of fairytales. And here, unlike in the up-front rewrite of the Manson history, the bad guys win, but get to be remembered as the good guys.

Oher clues: When Dalton is made over as an evil hippy, the wardrobe woman dresses him in a Custer jacket dyed dark brown, thus associating him with another famous adversary of the native peoples; and those who stayed for the closing credits were rewarded part-way through with Dalton's ad for Red Apple cigarettes. He now shares the screen with another double, a photo cut-out of himself, a 'standee', which will appear wherever Red Apples are sold. This is, then, a sort of modern equivalent of a cigar store Indian. After the director shouts 'cut,' Dalton angrily punches it to the ground.

That's pretty much the end of my remarks, but, sort of as an aside, especially when talking about cowboys rescuing princesses, one might also think of The Searchers and the way Taxi Driver references it, taking an already morally murky story and making it weirder, with Travis Bickle, dressed in cowboy shirts and boots throughout the film, giving himself a mohawk to face down an underage prostitute's pimp, himself dressed as an Indian, and bring forth a grotesque bloodbath to rescue this girl who doesn't want to be rescued. It's the cowboy deconstructed into psychopath as an indictment of the culture that celebrates him – which is basically what's going on here too.

Happy trails.

Comments

Post a Comment